A multitude of factors affect the final result of a 3D model. Time, budget, rendering speed and target audience all affect it.

Rendering Speed

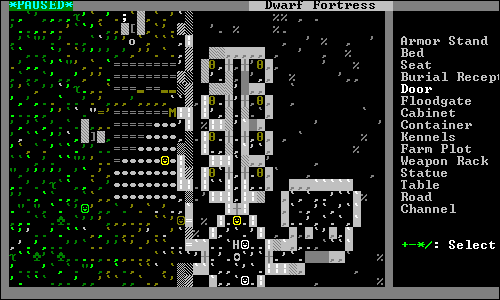

First and foremost is how the model is going to rendered; usually this means pre-rendered or real-time. Unsurprisingly, these terms describe what they actually mean. Real-time rendering involves rendering frames at a fast enough rate that the motion is still fluid and can also be interacted with at any point. Pre-rendering involves a very powerful computer (sometimes called render farms), rendering out each frame, one at a time and can take as much time as there is available, depending on the quality desired. Of course, the number of polygons for something that will be pre-rendered can be much higher than the number used to make something that is being rendered in real time. This comes at a sacrifice of quality but abstraction of detail techniques such as Normal mapping (which is sometimes used in films, but not regularly) can help even the disparity.

Here is an example of a high poly and low poly mesh. As you can see, the fewer polygons means the surface of the model is more faceted compared to the smoothness of the high poly version.

Video Games

If this were to be used in a video game, the high poly version would be "baked" into a Normal map and sometimes an Ambient Occlusion map which means converting all the high frequency detail into 2D textures which are then applied to the low poly model. The Normal map then works within the engine and helps define how the light reacts against the surfaces and gives the appearance of much more detail without the use of more polygons.

Movies

In a movie, the high poly model would be used with a Displacement map (for greater low frequency details) directly, with a different LOD (level of detail) model for the animators to actually use before rendering time. Of course, because of the greater number of polygons each frame can't be rendered within a 30th of a second. In fact, for the Transformers movie it took 38 hours to render just one frame of movement. In some extreme cases this can balloon to ridiculous degrees: in Transformers 3, during a scene in which a skyscraper is destroyed by a robot, took 288 hours per frame!

Overview

As can be seen, the difference the time available to render something dramatically changes what is and is not possible for the quality of the final model. Smaller productions such as advertising and TV series follow similar guidelines to movies but only allow for much shorter render times meaning the geometry still can't be as high fidelity as used in big blockbuster films but also isn't constrained to real-time rendering like games are.

Budget & Time

The budget of a production frequently influences how much time it has before release. As such, these are both related and affect the same parameters in regards to the final model.

Video Games & Movies

The budgets of modern video games and movies tend to both be in the tens of millions range. The time per model however will be drastically different and means that 3D models used in movies can have more details in comparison.

Children's TV Series

A TV program for children would have a much smaller budget and a greater time constraint than in video games or movies, requiring work to be done for weekly episodes. This greatly affects the final look of the product; typically they are simpler designs as shown here by The Octonauts. The simpler aesthetic enables the models to be less labor intensive and as such, cheaper and quicker to make.

Overview

Budgets typically affect the number of models as well as influencing their design. Larger amounts of money means more time and therefore more complicated and higher fidelity designs. Movies will usually have the biggest budgets and so their models can be complicated and high fidelity. Video games have similar but slightly smaller budgets and so their models are slightly less complicated and much lower fidelity and finally, TV series tend to have less time than either movies or games and so have less complicated models.

Target Audience

Whenever a commercial entertainment first enters pre-production, one of the foremost decisions companies need to make is what the desired demographic their product is aiming to sell to will be. These groups can be created by a combination of gender, age, socio-economic status amongst other things.

For Young Audiences

Young children's games, movies and TV programs (as well advertising aimed at them) will use much simpler models, with rounder edges and smoother forms. This, combined with other factors will decide the final model.

Overveiw

The final quality and fidelity of an asset for any part of a project is wholly dependant on the intention and constraints that the project itself is under. More money, time and rendering power allow for greater scenes of complexity - providing it's appropriate for the intended audience.

Here is an example of a high poly and low poly mesh. As you can see, the fewer polygons means the surface of the model is more faceted compared to the smoothness of the high poly version.

Video Games

If this were to be used in a video game, the high poly version would be "baked" into a Normal map and sometimes an Ambient Occlusion map which means converting all the high frequency detail into 2D textures which are then applied to the low poly model. The Normal map then works within the engine and helps define how the light reacts against the surfaces and gives the appearance of much more detail without the use of more polygons.

Movies

In a movie, the high poly model would be used with a Displacement map (for greater low frequency details) directly, with a different LOD (level of detail) model for the animators to actually use before rendering time. Of course, because of the greater number of polygons each frame can't be rendered within a 30th of a second. In fact, for the Transformers movie it took 38 hours to render just one frame of movement. In some extreme cases this can balloon to ridiculous degrees: in Transformers 3, during a scene in which a skyscraper is destroyed by a robot, took 288 hours per frame!

Overview

As can be seen, the difference the time available to render something dramatically changes what is and is not possible for the quality of the final model. Smaller productions such as advertising and TV series follow similar guidelines to movies but only allow for much shorter render times meaning the geometry still can't be as high fidelity as used in big blockbuster films but also isn't constrained to real-time rendering like games are.

Budget & Time

The budget of a production frequently influences how much time it has before release. As such, these are both related and affect the same parameters in regards to the final model.

Video Games & Movies

The budgets of modern video games and movies tend to both be in the tens of millions range. The time per model however will be drastically different and means that 3D models used in movies can have more details in comparison.

Children's TV Series

A TV program for children would have a much smaller budget and a greater time constraint than in video games or movies, requiring work to be done for weekly episodes. This greatly affects the final look of the product; typically they are simpler designs as shown here by The Octonauts. The simpler aesthetic enables the models to be less labor intensive and as such, cheaper and quicker to make.

Overview

Budgets typically affect the number of models as well as influencing their design. Larger amounts of money means more time and therefore more complicated and higher fidelity designs. Movies will usually have the biggest budgets and so their models can be complicated and high fidelity. Video games have similar but slightly smaller budgets and so their models are slightly less complicated and much lower fidelity and finally, TV series tend to have less time than either movies or games and so have less complicated models.

Target Audience

Whenever a commercial entertainment first enters pre-production, one of the foremost decisions companies need to make is what the desired demographic their product is aiming to sell to will be. These groups can be created by a combination of gender, age, socio-economic status amongst other things.

For Young Audiences

Young children's games, movies and TV programs (as well advertising aimed at them) will use much simpler models, with rounder edges and smoother forms. This, combined with other factors will decide the final model.

The final quality and fidelity of an asset for any part of a project is wholly dependant on the intention and constraints that the project itself is under. More money, time and rendering power allow for greater scenes of complexity - providing it's appropriate for the intended audience.